Of Art and Faith Intertwined

Posted:

Some places stay with you long after you leave.

For me, that place is the campus chapel at my university; the one that quietly kept me company through roughly three years of my post-grad life.

At the heart of the University of the Philippines Diliman (UP Diliman) campus, where pockets of green still resist the slow crawl of gray concrete across the last lungs of Metro Manila, stands a modernist sanctuary unlike any other nearby. Many parishioners fondly call the UP Chapel or the Parish of the Holy Sacrifice “the flying saucer,” for its distinctive dome-shaped roof that seems to hover above the ground. I, however, have always thought of it as a circle among rectangles: a gentle rebellion against the rigid lines of conventional architecture.

Leandro Locsin (1955)

For starters, what makes this place special is that the chapel is nestled strategically in a cradle of green, where the air smells cleaner, the silence softer. The decades-old acacias offer both shade and solace, their calm colors and foliage easing weary eyes and mind. Now and then, a cool breeze drifts through, light as breath, touching the skin just enough to remind you that you are still, and that these unique sensory experiences combine to allow you to be more inward with yourself and absorb the stillness of the moment.

It stood just across the dorm where I lived on campus; only a narrow two-lane road separating us. That small distance made all the difference. The nearness invited me to be present more often: during Sunday Masses, and the holy days, once on Easter Sunday, and during one of the Simbang Gabi. The chapel has always been a refuge. As a student fraught with chronic stress, it became the constant witness to both distress and delight; a place where I could pause and reflect, or enjoy my birthdays in silent solitude, away from the clamor of the world. Most days, I went there simply to breathe. With its wide open walls, it was the perfect safe space where I could shed the weight of expectations, if only for a while, and just exist: unhurried, unguarded, at peace.

I wouldn’t call myself a devout Catholic. I don’t read the bible, I often miss the Sunday obligations, and mostly, I let holy days pass unnoticed like the Pentecost, the Paschal Triduum, Easter, or the Simbang Gabi, for that matter. I’m trying to do my best, though. Yet, inside that chapel, I always find myself connected in prayer. Not out of ritual, but out of a quiet longing to commune with someone Higher, with God, even in my unpolished, imperfect way. Perhaps what makes those vulnerable moments even more profound for me is how the chapel itself seemed to pray with you. Every corner holding a piece of art coming together in a harmony of light, form, and adoration.

I wasn’t fully aware yet at the time, but after spending more than a year in that place and finally learning about its history, I came to understand that it was far more than its curious “saucer” shape that made the place very special against other structures in the area. I learned that I had been standing not just on hallowed ground, but in a place steeped in rich history and artistry. Here, one enters not just a place of worship, but in fact, the magnum opus of the nation’s finest talents in art and design.

The UP Chapel stands today as a permanent tribute to the talents and artistic legacy of several National Artists, some of whom were familiar names from my childhood; encountered in conversations at school, in old art textbooks that somehow stirred a sense of nostalgia. And so, imagine my shock and amazement when I finally learned about it. Here, their individual works converge to form its very framework, where each line, form, and curve a reflection of their collective artistry and shared mastery. Faith here is not confined to adoration alone, but also embedded in the very geometry of the space—an oblation.

To allow you to share in my fondness for the place, let me take you inside and discover for yourself the masterpieces within and the creative geniuses behind them. For my readers who haven’t had the chance to visit the church yet, I’ll try to inject my writing with as much detail and description as I can—and photos (some I’ve taken myself!)—so you yourself can paint a more vivid mental picture of the place itself. And for those who have already been there, perhaps this is also for you; I hope I could take you back and remind you of how truly special the place is. My hope is that, by the end, you come to see why the UP Chapel is not only a landmark but a living piece of remembrance that continues to inspire.

A Church-In-The-Round by National Artist for Architecture Leandro Locsin

Remember the flying saucer? That is what you’ll only see on the outside.

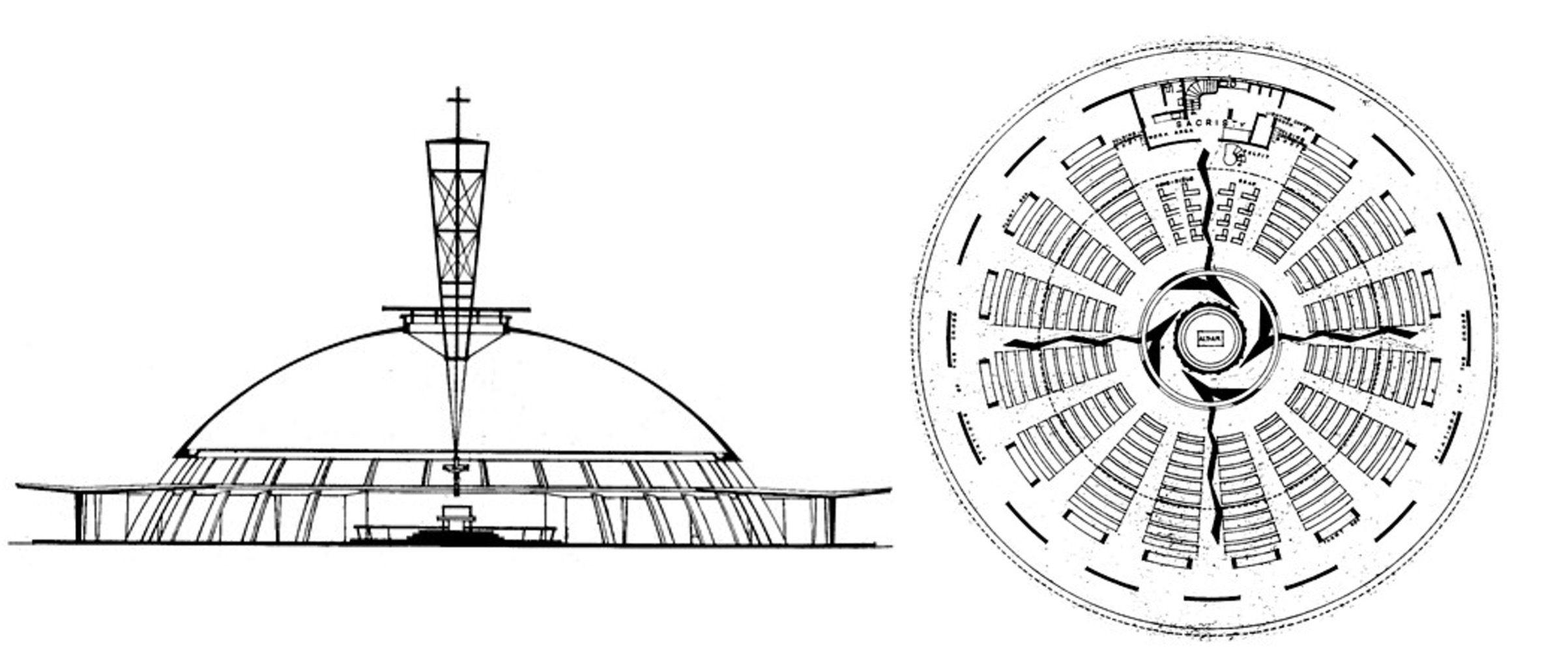

Inside, however, a breathtaking spatial experience. Picture a circular church with the altar at its center, not at the front. The pews radiate concentrically around it, with 14 equidistant open entrances encircling the perimeter; no doors. A thin-shell concrete dome (only 10 centimeters thick at the center) shelters the space, supported by a ring beam and thirty-two reinforced columns. Light pours in through the clerestory windows at the dome’s base, illuminating the interior sufficiently without the need for artificial brightness during the day. The clerestory and the open entrances further allows fresh air to flow through unchallenged, creating a sense of openness. At the dome’s apex, a circular skylight, called an oculus, opens directly to the sky, supporting both the triangular bell tower above and the suspended Crucifix below. The oculus perhaps suggests a rich symbolism of the firmament, as if it is a boundary through which the heavens can peer through into you and the sacred celebration that unfolds below.

Leandro Locsin (1955)

National Artist Locsin’s 1955 design was inspired by traditional Filipino sensibilities reinterpreted through post-war aesthetics. Its radical circular plan defied the traditional Baroque and Gothic influenced designs familiar to many Catholics, as well as the linear orientation of the Catholic rites. But that defiance was deliberate. Locsin envisioned a church without corners, without hierarchy, so that the laity, us, encircling the altar, shared equal intimacy to the mystery of the Eucharist. And no doors, so that anyone seeking refuge feels welcomed and invited, anytime.

The unique architecture was, at the time, a first of its kind in the Philippines, and in Asia: a structure without precedent in regional architecture. It was a revolution in ecclesiastical design; intentional, radical, and visionary. While many Filipino architects of the time followed the aesthetics of contemporary American designs, Locsin’s “flying saucer” remains a singular triumph of Filipino Modernism.

The Double Figure Crucifix of Christ by National Artist for Sculpture Napoleon Abueva

At the very heart of the chapel are several works by National Artist Abueva, a first in church art executed in neorealist style. Floating above is a crucifix unlike any other. Entitled Christ Crucified and Christ Resurrected, it reveals Abueva’s mastery in giving Christ a form to show both His humanity and divinity. The massive wooden centerpiece presents two frontal figures joined back-to-back on a single cross: on one side, the stripped Christ with His head bowed in death (Christ the Victim), His sinews and muscles carved in stark realism and clothed only with a simple loincloth; on the other, a robed Christ in full tunic (Christ the Priest) erected in symmetrical verticality, His head lifted high in triumph, embodying His purity and priesthood. With arms outstretched in eternal embrace, the risen Christ seems to hover weightlessly, as if caught between ascent and descent.

Napoleon Abueva (1957). Hardwood.

Directly beneath stands the Prestól, the marble altar table Abueva completed twenty-two years later after he created the crucifix, in 1957. Its reliefs depict The Sermon on the Mount on one side, and scenes of Christian community on the other. Illuminated by the soft light filtering through the oculus above, Abueva’s installments evoke a profound imagery between suffering and glory, pain and redemption; transforming my every visit into an enriching meditation on the mystery of faith.

Napoleon Abueva (1979). Marble.

The River of Life Floor Terrazzo by National Artist for Visual Arts Arturo Luz

Perhaps the very first artwork to greet every pilgrim visiting the UP Chapel (aside from its dome structure) is an intricate terrazzo floor made with exquisite restraint and quasi-mathematical precision, guiding the ingress from the gates of the Church and into the altar dais. Composed of inlaid mosaics of black, white, and gray marble chips, it forms an abstract mural that evokes a flowing river both in form and meaning. National Artist Luz’ design portrays the stream of Christian spirit: the river as a symbol of life flowing from God (at the altar), the source of all creation.

Arturo Luz (1955). Mosaic Marble Chips.

Angular, dynamic zigzag patterns of the River of Life radiate from the altar at the chapel’s center, coursing down to the sacristy and branching outwards to the three Church entrances: one along G. Apacible Street and two along F. Agoncillo Street, that open into the main university roads. I cannot help but follow it with my eyes every time I visit the place, and now being more mindful in tracing its movement, as though I am being drawn into the same current that unites faith, culture, and a sense of oneness.

Murals of the Stations of the Cross by National Artist for Painting Vicente Manansala in collaboration with National Artist for Visual Arts Ang Kiukok

Between the pillars sustaining the church dome, are fourteen walls each bearing a mural from the Via Crucis or Stations of the Cross, rendered in raw and expressive Cubist elements by Vicente Manansala, assisted by a then-younger Ang Kiukok. The two artists undertook the monumental task of painting several mural-sized Stations of the Cross, with each panel spanning the full height and width of the rectangular walls beneath the lower roof. To complete this vast project, Manansala enlisted his student Ang Kiukok, who would later follow his mentor’s modernist vision, and join him among the Order of National Artists.

Vicente Manansala and Ang Kiukok (1955-56). Oil on Masonite.

In total, they produced fifteen murals encircling the church: fourteen depicting the traditional Stations and one added by Manansala to portray the Resurrection, painted on the sacristy stone. Each panel, measuring fourteen by nine feet, was executed in oil on masonite boards, a choice that allowed for vivid color saturation and durability over time. Their bright tones, from ochres and reds to deep blues and dark browns, remain remarkably vibrant up to this day. As I moved past each station, I could only adore in quiet reflection, as I retrace my own personal Stations that I have taken and those that I will continue to take.

Just when I thought the Easter eggs had ended there, I learned that the Church once again welcomed another kind of talent; this time filling its space not with art to behold, but with art to be heard.

A Concert Premier by National Artist for Music José Maceda

Who has such a crazy imagination these days? At the time, perhaps only a mind like that of National Artist Maceda could, whose ambitious musical composition in 1968, Pagsamba (Worship), merged faith and avant-garde experimentation. Conceived as a site-specific ritual, it was at once a Christian Mass and a theatrical performance. From what I’ve read, it involved over 200 singers and instrumentalists consisting of: 100 mixed voices, 25 male voices, 8 each of suspended agung and gandingan (gongs), and 100 players performing on ungiyong (whistle flutes), balingbing (bamboo buzzers), palakpak (bamboo clappers), tagutok (bamboo scrapers), and bangibang (yoke-shaped wooden bars struck with beaters).

José Maceda (1968)

The performers were scattered among the audience, all facing the altar where the conductor led the ceremony. This spatial arrangement, combined with the sheer number of instruments, produced vast tonal layers that would sound different to each listener depending on their position in the church. This arrangement perhaps made the experience more communal as if it were a ritual held in a rural village, demanding a rare kind of social participation to performers and audience alike; being both a concert and a Christian Mass. One can only imagine the sensory intensity: music reverberating from every direction, the dome above trapping and amplifying the sound. We can only wish we were there; but until then, your imagination is as good as mine.

To this day, the UP Chapel is declared as both a National Historical Landmark by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, and a National Cultural Treasure by the National Museum of the Philippines. It also remains as the only structure in the country to feature the works of five National Artists (six, if we include Maceda) none of whom, at the time, had been inducted into the Order. All of these make the UP Chapel a singular artistic achievement. The Order of National Artists (Orden ng Pambansang Alagad ng Sining) was established only in 1972, with these artists receiving the recognition well into the late 20th century and beyond. Perhaps it was by grand design that, decades before their recognition, these artists’ paths had already crossed to create a shared legacy of art and faith intertwined. And I think that is powerful.

Perhaps that’s why this place has stayed with me; it holds an indescribable feeling of peace and familiarity that I rarely find elsewhere. Here, one can really close their eyes and just simply take in the slowness and stillness of life, unhurried. The arts deepen the experience, for sure, which reminds me that the purpose of art was once not to shock or disturb, but to elevate the soul. I do wish you the same feeling when you visit.

These days, people rarely give it a second glance. So, the next time you hear Mass, stop for a prayer, or simply drop by, you may want to pause and take a moment to appreciate the space. Maybe you might consider including it in your next Visita Iglesia. I can promise that the experience in the place will be enriching, with each visit you discover and learn something new about art, faith, and yourself.

Pax vobis!

If you’d like to know more about the UP Chapel, the following FAQs may help:

- Address: Laurel Ave, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City

- Website: parishoftheholysacrifice.ph

- Mass schedules

(Nabua, 10/2025)

Leave a Comment